Do you believe wellbeing means the same thing to everyone?

If we all enjoy and value different things, how is it possible to understand happiness? Doesn’t that make measuring happiness extremely difficult?

Positive psychology is concerned with how people can do well, be well, feel well, and flourish over the long term. And subjective wellbeing (SWB) is one way to understand what this means to different people.

This article explores the origins of SWB, its components, how we can measure it, and more.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Happiness & Subjective Wellbeing Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify sources of authentic happiness and strategies to boost wellbeing.

According to Diener (2000, p. 34), SWB is “people’s cognitive and affective evaluations of their lives.”

Veenhoven (1997, p. 34) describes it similarly: “how good [life] feels, how well it meets expectations, how desirable it is deemed to be, etc.”

In general, the concept involves two broad elements (Kashdan, 2004):

‘Cognitive appraisal’ describes how we consider our global (overall) life satisfaction and our satisfaction with specific domains (e.g., family life, career, and so forth).

‘Affective appraisal’ concerns our emotional experience. High SWB is the experience of frequent and intense positive states (e.g., joy, hope, and pride) and the general absence of negative ones (e.g., anger, jealousy, and disappointment).

When we think about and appraise our lives, we compare our perceived status against our own standards of desirability. This is the subjective element of cognitive appraisal.

Likewise, different things are associated with positive affect for different people. This is the subjective aspect of affective appraisal.

SWB encompasses a vast array of different concepts, from fleeting experiences in our day-to-day lives to much broader global judgments that we make about our lives as a whole (Kim-Prieto, Diener, Tamir, Scollon, & Diener, 2005). It is typically considered a hedonic as opposed to a eudaimonic concept (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Huta & Waterman, 2014).

Professor Ed Diener is one of the world’s foremost SWB researchers, coining the construct in his seminal 1984 article Subjective Well-Being.

Ever since, he has continued to study the subject from a positive psychology perspective. With a career spanning more than 25 years, his vast contributions to the field have earned him the nickname “Dr. Happiness.”

Diener & Diener (1996) found that most people reported a positive level of SWB and satisfaction with important life domains. In 86% of the 43 nations examined, average subjective wellbeing was higher than neutral.

Focusing on very happy individuals, Diener and Seligman (2002) screened US undergraduate students for happiness to examine factors that might influence high levels of happiness.

Using multiple instruments that included the Satisfaction With Life Scale, their findings revealed that “while there appears to be no single key to high happiness… very happy people have rich and satisfying social relationships and spend little time alone relative to average people” (Diener & Seligman, 2002, p.83).

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover authentic happiness and cultivate subjective well-being.

Download PDF

By filling out your name and email address below.

So if we wanted to measure our SWB, what precisely would we evaluate?

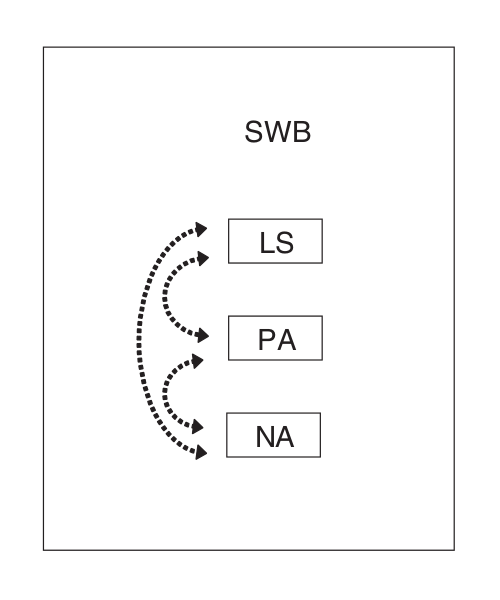

SWB is most often thought of as having three components (Diener, 1984; Busseri & Sadava, 2011; Tov & Diener, 2013):

The diagram below is one possible way to represent the three components visually, where LS = life satisfaction, PA = positive affect, and NA = negative affect.

Source: Busseri & Sadava, 2011, p. 292

They are considered distinct but interrelated because individuals tend to make judgments of satisfaction (e.g., “My life is fantastic”) using their emotional experiences (e.g., “I’m feeling great right now”; Tov & Diener, 2013).

Together, the three components make up the tripartite model of SWB (Busseri & Sadava, 2011). The two affect components are typically assessed independently of the life satisfaction component, using different scales.

Busseri and Sadava’s (2011) article covers several potential ways the three SWB components may be linked. The diagram above shows only one of them – a ‘separate components’ framework that assumes no relationships between PA, NA, and LS.

There are, however, other frameworks that have been suggested, in which the components make up:

A hierarchical construct in which a higher order factor SWB correlates positively with PA and LS, and negatively with NA.

A causal system model where, among other things, LS is influenced by PA and NA.

A composite model where all three components combine to contribute to SWB together.

A configuration framework, which views SWB as an integrated system of LS, PA, and NA, all of which are differently configured within distinct individuals (Shmotkin, 2005).

If you find this interesting and would like to learn more, I would highly recommend Busseri and Sadava’s (2011) article.

There are many reasons why subjective wellbeing matters to individuals and society as a whole.

Our affective experiences and overall emotional wellbeing are central to our quality of life as individuals (Skevington & Böhnke, 2018).

People who feel satisfied with their lives and frequently experience good feelings such as joy, contentment, and hope are more inclined to be seen as enjoying a high quality of life.

Measures of SWB can be used to inform policy decisions, academic curricula, and social initiatives that contribute to a better quality of life for citizens and communities across the world (OECD Better Life, 2013).

Gross domestic product (GDP) alone is not an adequate measure of life quality at the national level, although research suggests that it may have some impact on SWB through various mechanisms (Diener, Tay, & Oishi, 2013). It is generally agreed that SWB offers a more comprehensive measure of a nation’s wellbeing by extending the concept beyond merely material concerns and considering individual perspectives rather than outsider judgments.

For a great discussion on SWB and GDP as indicators of human progress, I recommend this article by Richard Easterlin (2019).

An interesting question, and view review it with the following studies.

Mental health is critical to SWB and vice versa. Very crudely, mental health can be considered the absence of negative psychological symptoms and the presence of positive ones (Abdel-Khalek & Lester, 2013).

What’s important to note here is that the absence of illness and disease is not considered enough for people to have good mental health, and it’s where SWB comes into the definition.

By recognizing the role of feelings such as joy, life satisfaction, fulfillment, purpose, and contentment in life, we have a more holistic mental health concept. In turn, we can better understand how to facilitate its development in individuals and populations (Keyes, 2006).

Happiness is often equated with SWB in the literature, media, and more. In recent times, however, the latter is more widely thought of as the main affective component of the former (Machado, de Oliveira, Peregrino, & Cantilino, 2019).

This means that SWB encompasses more than just happiness. By incorporating life satisfaction into SWB measures, we include consideration of past experiences and future expectations.

As a discipline, positive psychology is focused on how virtues, strengths, and skills can help individuals and communities thrive and flourish. It involves topics, such as meaning, mindset, happiness, gratitude, and compassion, that can play a role in wellbeing and a meaningful, good life.

SWB falls under one of the three basic orientations that facilitate wellbeing (Seligman & Royzman, 2003):

Typically considered a hedonic form of happiness, SWB is central to the first orientation: a life of pleasure.

Positive psychology studies on SWB cover a growing range of topics (Diener, Oishi, & Tay, 2018):

SWB measures and methods. Currently, the vast bulk of SWB assessments are based on self-report scales and measures. While these measures have been relatively reliable, academics have raised concerns about methodological issues such as validity, so we can likely expect to see more research in this area soon.

Factors underpinning SWB. The role of genetics, income, personality, community, societal factors, and more have long been a key area of interest for SWB and positive psychology researchers. One example is Deaton’s (2008) Gallup World Poll study of income, wellbeing, and health, which linked SWB to national income.

Theoretical SWB processes. Studies of this type explore and examine the mechanisms underpinning subjective wellbeing, for example, biological theories of SWB, goal satisfaction, and mental-state theories. Headey’s (2010) study on genetics and SWB, for instance, found that many people who experience serious adverse events don’t always go back to their original baseline levels of subjective wellbeing.

SWB outcomes. This area of research concerns how subjective wellbeing impacts us. Some exciting new directions being explored are its impact on health and whether too much SWB can be detrimental to motivation (De Neve, Diener, Tay, & Xuereb, 2013).

SWB between countries. Research here looks at cross-national differences in average SWB, as well as issues like whether SWB predictors vary cross-culturally (Diener & Tov, 2012).

What interests you?

So, what is life satisfaction exactly? According to Dutch happiness expert Veenhoven (2015, p. 6), it refers to “the degree to which a person evaluates the overall quality of his or her present life-as-a-whole positively.”

Veenhoven (2012) presents a fourfold matrix to unpack the subjective life satisfaction concept further.

His framework involves two axes: from short-lived to enduring satisfaction, and from overall satisfaction to satisfaction with life domains.

| Passing | Enduring | |

|---|---|---|

| Part of life | 1. Pleasure | 3. Domain satisfaction |

| Life as a whole | 2. Top experience | 4. Happiness |

Source: Adapted from Veenhoven (2012, p. 21)

Instant satisfaction/pleasure is a passing, often sensory experience of life aspects. Examples include listening to a great piece of music or eating a delicious slice of cake.

Domain satisfaction is enduring, continued appreciation of a life domain – being satisfied with your academic career, for instance, or your marriage.

Top experience describes passing satisfaction with your life overall; short-lived but intense, Veenhoven (2012, p. 4) describes one example as “a moment of bliss.”

Finally, core meaning/happiness refers to enduring, overall satisfaction with life. Veenhoven considers this ‘durable’ and argues that this is the real meaning of ‘life satisfaction.’

We can now understand the subjective wellbeing concept in a little more detail.

In short, life satisfaction is integral to subjective wellbeing (Veenhoven, 2012).

The cognitive and affective components of SWB are assessed using different scales and measures. These often involve self-report instruments but can also be evaluated by comparing the results with other variables (Layard, 2010):

Friends’ reports

Plausible wellbeing causes

Some likely wellbeing outcomes

An individual’s physical functioning, e.g., cortisol levels

Brain activity measures

The PANAS is a self-report questionnaire comprising two separate subscales, one measuring positive affect and one measuring negative affect (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988; Medvedev & Landhuis, 2018).

Each scale includes 10 adjectives that relate to different affective states, such as “hostile,” “alert,” “jittery,” and “proud.” Using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 is “Not at all/Very Slightly” and 5 is “Extremely,” participants rate the extent to which they feel each emotion.

Read more about the PANAS in greater depth.

Another commonly used measure of affect, the SPANE, was developed by Diener et al. in 2009. It measures both pleasant and unpleasant emotional feelings, as well as other positive states, such as flow and engagement, physical pleasure, and interest. Similar to the PANAS, it works by presenting 12 adjectives that the participant considers; examples include “joyful,” “afraid,” and “contented.”

All items are scored using a 5-point Likert scale that spans from 1 (“very rarely or never”) to 5 (“very often or always”). The positive feelings score (SPANE–P) and negative feelings score (SPANE–N) yield positive and negative figures, respectively, which allows you to calculate your overall affect balance score (SPANE–B).

Your SPANE-B will be a figure between -24 (the unhappiest possible score) and 24 (the happiest possible rating). Find the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience in our Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin’s (1985) Satisfaction With Life Scale is a compact questionnaire for measuring global life satisfaction.

It looks specifically at the life satisfaction construct and doesn’t include items for affect. With good internal consistency and temporal reliability, it consists of five statements where participants can indicate a level of agreement on a 7-point scale.

Where 1 = “Strongly Disagree” and 7 = “Strongly Agree,” a higher score indicates higher life satisfaction.

Example items include:

The conditions of my life are excellent.

So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life.

You will find the Satisfaction With Life Scale in our Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

Hills and Argyle (2002) developed the OHQ as an improvement on the Oxford Happiness Inventory, which was being used at the time to measure SWB (Kashdan, 2004). Participants use a 1–6 scale to report how much they agree with 29 items, where 1 indicates the strongest disagreement possible and six, the strongest agreement.

It includes questions on happiness, such as the following:

I have very warm feelings towards almost everyone.

There is a gap between what I would like to do and what I have done.

I do not have a particular sense of meaning and purpose in my life.

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises, activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!”

— Emiliya Zhivotovskaya, Flourishing Center CEO

We’ve got great PDF exercises, activities, and interventions related to subjective wellbeing on our website designed to help you or your clients move toward greater SWB. Here are a few.

Because frequent positive affect is one key aspect of SWB, interventions centered on pleasant activities can be one way to work on your overall wellbeing (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013). This exercise aims to help you recognize what intentional practices, circumstances, and situations put you in a positive emotional state, enabling you to engage in them more often for improved SWB.

The first step in the Have a Good Day Exercise is to deliberately take note of your good and bad days to stimulate awareness of what makes them good or not. Continuing this activity for at least two weeks, you make a note of what you do each day and rate the day overall on a scale of 1 (“It was one of the worst days of my life”) to 10 (“It was one of the best days of my life”).

At the end of this period, you analyze your information and ask yourself a series of guided questions, e.g., “Are there certain activities, situations, or circumstances that consistently seem to contribute to a negative evaluation of a day?”

The final part of this activity involves creating a detailed plan based on your reflection. How can you make more of your days into good days?

The Have a Good Day Exercise is available in full as part of the Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

According to various researchers, our SWB may be somewhat dependent on the values that we prioritize (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000; Sortheix & Lönnqvist, 2014, 2015). Understanding our values can put us in a better position to take steps toward those that are important to us. This is why values clarification may help improve SWB.

This Values Clarification Worksheet gives you 10 different life domains and a set of prompts for each. The goal of the activity is to help you think about your potential life goals per domain. The categories are romantic relationships, leisure and fun, job/career, friends, parenthood, health and physical wellness, social citizenship/environmental responsibility, family relationships, spirituality, and personal development and growth.

The Positive Emotion Brainstorm exercise is designed to help you think of potential ideas for increasing the frequency and intensity of positive emotions in your day-to-day life. By targeting the types of positive feelings that you experience the least, you can try to increase your positive affect and SWB.

It is based on Fredrickson’s (2001) broaden-and-build theory, which suggests that positive emotions expand our awareness and encourage us to think and behave in newer, more varied ways. There is substantial evidence that this may help improve our resilience and wellbeing, among other psychological resources (Fredrickson, 2003).

Step 1 gives you a list of positive emotion groups to choose from, such as:

Grateful, appreciative, or thankful

Interested, alert, or curious

Love, closeness, or trust

In the next step, you write about three emotions you choose from the group you experience the least. Finally, you can use the prompts provided in Step 3 to think about ways you might increase the opportunities in your life to experience them.

The Positive Emotion Brainstorm is available in full as part of the Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

What makes one person happy isn’t necessarily going to make another person feel the same way. In the same regard, an individual may look at their life and feel entirely satisfied with it, while another would consider it inadequate.

Consider Gemma, for example:

Gemma has a very active lifestyle. She runs, plays tennis, swims, and feels proud that she performs brilliantly in all of these activities. She thinks that regular exercise and competition help her stay optimistic, in good physical health, and in control of everything. In her free time, she writes a blog about automotive mechanics, a subject she feels passionate about.

Gemma is also a highly involved mother to her children, a loving daughter, and feels she is in a happy marriage. While she sometimes feels anxious about finances or lonely when her husband is abroad, on the whole, she experiences more positive feelings than negative: joy, love, interest, pride, and optimism about her future.

In this example, we can see how Gemma has more frequent and intense positive emotions than negative ones. She goes out of her way to engage in activities that cause these emotions (playing sports, spending quality time with her children and parents, and writing her blog), and when she stops to reflect, she feels satisfied with her life as a whole.

Let’s look at another example:

Vikram is a very passionate climate change researcher. He lives in an Antarctic base station with a skeleton crew of fellow researchers.

He’s not super active and never did well at any team or individual sports, doesn’t have children, and isn’t married. He isn’t in touch with his family as much as he would like – it’s a bit tough in the Antarctic – but he cultivates close friendships with the rest of the research team, borne out of shared interests.

Every day at work, Vikram feels immense awe at the beauty of his surroundings and the many things he’s lucky enough to observe in the field. He constantly feels inspired and intrigued by his team’s research findings and so grateful to have worked hard and earned this opportunity. He can spend hours absorbed in his experiments and analyses.

When Vikram thinks about his life overall, he’s proud of his accomplishments and happy that he’s helping solve the global climate change problem one step at a time.

As we can see, Vikram has pretty different values from Gemma. As a whole, however, he’s extremely satisfied with his life, and he derives significant enjoyment from the activities he pursues. He feels he’s working with a larger sense of purpose and making significant progress toward the goals that matter to him.

Two different people, two distinct lives; both experiencing high subjective wellbeing.

Perhaps the most noteworthy evidence in support of an IQ–SWB linkage is Diener and Fujita’s (1995) finding, which revealed a 0.17 correlation between the two. Although they only examined participants in developed economies, their results suggested that IQ may be one of numerous “personal resources” that predict SWB.

In general, however, there is a widespread academic consensus that no significant relationship exists between cognitive intelligence and subjective wellbeing (Gottfredson, 2008; Grossmann, Na, Varnum, Kitayama, & Nisbett, 2013). Instead, it’s emotional intelligence (EQ) that appears to be a powerful SWB predictor, particularly of SWB’s cognitive component (Sánchez-Álvarez, Extremera, & Fernández-Berrocal, 2016).

Read more about this in Sánchez-Álvarez et al.’s (2016) meta-analysis on EQ and SWB: The Relation Between Emotional Intelligence and Subjective Well-being.

Add these 17 Happiness & Subjective Well-Being Exercises [PDF] to your toolkit and help others experience greater purpose, meaning, and positive emotions.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Work or job satisfaction is a SWB component that has been found to correlate positively with life satisfaction (Bowling, Eschleman, & Wang, 2010). While the vast bulk of studies into work satisfaction and SWB are correlational, the literature does include several theories that address the relationship between the two.

Heller, Judge, and Watson (2002, p. 816) suggest a spillover hypothesis, arguing that “job experiences spill over into other spheres of life, and vice versa, suggesting that a positive relationship exists between the two variables.” When examined further, researchers found experimental evidence supporting this theory by discovering a bi-directional relationship between life satisfaction and job satisfaction (Unanue, Gómez, Cortez, Oyanedel, & Mendiburo-Seguel, 2017).

This relationship may be influenced by workers’ psychological needs fulfillment. When they felt their needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence were satisfied, they were happier, more productive, and more engaged (Unanue et al., 2017).

So, we see some potentially useful implications for ways that organizations can help employees (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Van den Broeck, Ferris, Chang, & Rosen, 2016; Unanue et al., 2017):

Creating conditions under which they feel that their behavior is meaningful and voluntary may satisfy employees’ needs for autonomy.

Making them feel their behavior is effective and efficient may satisfy their psychological need for competence.

Considering what makes employees feel appreciated, understood by, and connected to significant others could fulfill their need for relatedness.

The more we know about subjective wellbeing, the more equipped we are to start improving our happiness overall. Hopefully, this article has given you some more insight into one of positive psychology’s most central concepts, as well as some advice on how to boost your SWB.

If you can begin to create more positive moments in life, identify your fundamental values, and move toward your goals, you’re well on the way to greater life satisfaction and a positive affect balance. So, what are your tips for improving wellbeing? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Happiness Exercises for free.

References